Plenary session remarks at New England American Studies Association Conference, Plimoth Plantation, Plymouth, MA

Plenary session remarks at New England American Studies Association Conference, Plimoth Plantation, Plymouth, MA

November 4, 2011

(Click on images for larger versions)

A place like Plimoth Plantation is always good to think with, but I’m particularly glad to have been asked to reflect on it now, because as I thought about it this past week, I realized that it let me integrate things I’ve been considering over the whole course of my 20-year intellectual trajectory, which I’ll try to compress as ruthlessly as possible into a few minutes here.

It was particularly interesting to do this because I was doing a lot of it by candlelight. I live in western Mass. and we were without power for several days this week after getting nearly two feet of snow just before Halloween. So I’ll try to show why that all connects, and what emerging meanings and uses it suggests to me for this place, the myths associated with it, and the tensions and knowledge embodied in those myths.

I’m going to talk about Plimoth in relation to two terms: “occupation” (and re-occupation) and “refuge,” in both its social/spiritual sense and in the biological sense of refugium, or an isolated place that provides specialized conditions and habitat for species that can no longer survive elsewhere.

I’m going to talk about Plimoth in relation to two terms: “occupation” (and re-occupation) and “refuge,” in both its social/spiritual sense and in the biological sense of refugium, or an isolated place that provides specialized conditions and habitat for species that can no longer survive elsewhere.

My trajectory as a scholar started with studying historical (mostly military) reenactment in the 1990s. I came away from that with a sense of reenactment as a highly complex response to and expression of ambivalence about many things in contemporary society – for example, changing gender roles, the uneasy patriotisms and nationalisms of the post-Vietnam era, and the iconic figure of the American citizen-soldier.

But through all of this there was also a strand of ambivalence about the broader effects of capitalism and modernity, and I came to see reenactment within a much longer history of anti-modernism. In this case, it was framed within an explicitly avocational world. Reenactors created a weekend refuge rather than a resistance movement, which gave them a sense of having escaped temporarily from the modern capitalist world rather than having to mount any kind of direct challenge to it.

I did, though, encounter quite a number of younger Gen X and Gen Y reenactors who were becoming more professional about their avocation and finding ways to turn it into an occupation, usually at places like Plimoth Plantation and other living history sites. This made the weekend refuge something more permanent, but also brought it back into closer contact with the realities of the postindustrial American economy, in which knowledge, service, experience, and cultural production of all kinds are increasingly gobbled up into revenue-generating projects.

That moved me into studying historical interpretation as a professional endeavor, which I did through an ethnographic study of public historians at a large urban national park. I saw similar demographics and motivations at work in these interpreters, and although they were decidedly more left-leaning and overtly critical of capitalism than the reenactors, they were also generally unwilling to risk the relative security of their jobs and professions by bringing their critiques too directly into their working lives.

To my eye, this neutered the critical historical insights that they were intellectually fully capable of making, something that Richard Handler and Eric Gable have also noted in the case of interpreters at Colonial Williamsburg. As I looked around the public historical world, I saw a pattern of drawing lines around “history” that tended to stop short of historicizing or problematizing the kinds of tourism, branding, and economic redevelopment efforts that public historians’ work is so often embedded within.

To my eye, this neutered the critical historical insights that they were intellectually fully capable of making, something that Richard Handler and Eric Gable have also noted in the case of interpreters at Colonial Williamsburg. As I looked around the public historical world, I saw a pattern of drawing lines around “history” that tended to stop short of historicizing or problematizing the kinds of tourism, branding, and economic redevelopment efforts that public historians’ work is so often embedded within.

I was looking largely at full-time employees within the National Park Service, which is probably the closest equivalent to the tenured professoriate that exists in public history. But even those relatively secure knowledge workers were reluctant to expose their occupational lives too directly to the sharp realities of the postindustrial cultural marketplace. Those without any job security – people in the ever-growing ranks of “contingent” workers within the academy and other areas of the knowledge industry – have far more reasons to be leery.

Plimoth Plantation provided a rather high-profile example of the volatility and contingency of this kind of work when, after the economic downturn in 2008, it “riffed” most of its curatorial staff in an attempt to stay afloat economically. The many satisfactions of this kind of work come with a price, and part of that price is a very tenuous position in an increasingly lean and mean model of economic survival. Refuges are luxuries in our current (and probably future) economy, as resources become scarcer, the concept of a publicly-funded public good comes under widespread assault, and the middle-class prosperity that has historically sustained places like Plimoth Plantation and avocations like reenacting continues to erode.

My most recent project, though, gives me hope that this dark moment may in fact be the beginning of a turning point. For the past couple of years, I’ve been working on an Ethnographic Landscape Study for Martin Van Buren National Historic Site in the Hudson River Valley, a Presidential site that has recently expanded its boundaries to incorporate most of Van Buren’s post-Presidential farm estate. The farmland is currently being cultivated by a large CSA (Community Supported Agriculture) farm, and so the park, which is used to thinking of itself as a purely historical site, is having to reenvision itself as to some extent an active participant in the working agricultural landscape of the area.

My study addresses the complexities of reintegrating past and present within that landscape, which has a long regional history of being shaped by both the industrialization of American agriculture and the backlash against industrialization in the form of pastoral tourism. The Hudson Valley was of course one of the first places in the country that Americans turned to in search of experiences of countryside that could evoke supposedly simpler ways of life and foundational national values.

The depth of that anti-modernist history is striking – it began as early as the first decades of the nineteenth century – but so is the fact that a sharp distinction between past and present modes of farming didn’t really take place until after World War II. It wasn’t until then that the “olde tyme” farms that tourists loved to visit were no longer viable in a fully industrialized, commodity-oriented farm sector. Not coincidentally, that was the period when Henry Hornblower created Plimoth Plantation, during the boom in heritage tourism in the U.S., all facilitated by that quintessential technology of American industrial modernity, the automobile. Because farming was such a widespread way of life in the nation until after the turn of the 20th century, the great majority of historic sites had some association with agriculture, and farm landscapes and skills came to be – and remain – a kind of shorthand signifier for “yesteryear.”

The depth of that anti-modernist history is striking – it began as early as the first decades of the nineteenth century – but so is the fact that a sharp distinction between past and present modes of farming didn’t really take place until after World War II. It wasn’t until then that the “olde tyme” farms that tourists loved to visit were no longer viable in a fully industrialized, commodity-oriented farm sector. Not coincidentally, that was the period when Henry Hornblower created Plimoth Plantation, during the boom in heritage tourism in the U.S., all facilitated by that quintessential technology of American industrial modernity, the automobile. Because farming was such a widespread way of life in the nation until after the turn of the 20th century, the great majority of historic sites had some association with agriculture, and farm landscapes and skills came to be – and remain – a kind of shorthand signifier for “yesteryear.”

In our present moment of anxiety about peak oil, climate change, and economic breakdown on many levels, I see signs that this nostalgic approach to farming may be changing. With each unexpectedly damaging “weather event,” like last week’s freakish October blizzard, I hear more people wondering whether this is the “new normal” and whether old is in fact the new new – that is, whether reading by candlelight, having food put by for times of hardship, living in less energy-intensive ways, and recultivating smaller-scale community resources of all kinds may become essential once again to everyday existence.

In this changing climate, visitors and practitioners alike may be starting to reassess the historic landscapes of places like Plimoth in search of ideas, knowledge (about archaic skills and also about how we got into the various dilemmas we’re in now), and possible solutions. Scholars have become used to thinking of historic sites and interpretations as creating a “usable past,” but the past may be starting to be usable in a literal as well as a strategic or symbolic sense.

What is just beginning to happen, I think, is that some farmers themselves are finding ways to connect their work with the refugia that historic sites have somewhat inadvertently or inchoately created and preserved. In the old northeast, where the movement of people away from farms starting in the early 19th century prompted much of the nostalgia and anxiety that gave rise to the preservation and heritage tourism movements in the first place, the number of farms and farmers is on the rise again after a very long decline.

The new farms are smaller and less industrialized and the farmers younger than their predecessors, and many of them see themselves as part of a global movement toward the relocalization of food supplies, the reestablishment of regional foodsheds, and the revalorization and reskilling of farming as an occupation, challenging the dominant model of agriculture in which farmers essentially just produce an industrial raw material for processing. Many of these younger farmers are making trenchant critiques of industrial capitalist modernity, and in this, they are fully aligned with the young activists who are spearheading the “Occupy” movement and demanding an undoing and radical rethinking of the structures of wealth production that have been created in the last few decades. They are challenging the same market-driven logic that has made knowledge about the past into largely just a branding opportunity or a recreational or avocational encounter.

The new farms are smaller and less industrialized and the farmers younger than their predecessors, and many of them see themselves as part of a global movement toward the relocalization of food supplies, the reestablishment of regional foodsheds, and the revalorization and reskilling of farming as an occupation, challenging the dominant model of agriculture in which farmers essentially just produce an industrial raw material for processing. Many of these younger farmers are making trenchant critiques of industrial capitalist modernity, and in this, they are fully aligned with the young activists who are spearheading the “Occupy” movement and demanding an undoing and radical rethinking of the structures of wealth production that have been created in the last few decades. They are challenging the same market-driven logic that has made knowledge about the past into largely just a branding opportunity or a recreational or avocational encounter.

Knowledge about the past has value aside from its instrumental uses, of course. And the environmental and population changes of the past century create new limits and new challenges that preclude any kind of simplistic return to an imagined agrarian utopia. But my hope for Plimoth Plantation and the countless other American historic sites with some connection to farming is that they can find ways to marry the spirit of stewardship, inquiry, and discovery that has always characterized them with a more engaged sense of mission within the growing “sustainable agriculture,” “local food” and “transition” movements.

There are signs of this happening around the old northeast: CSA farms operating at Trustees of Reservations sites in Massachusetts, farmers markets at various historic sites throughout the Blackstone River Valley National Heritage Corridor just west of us, the extensive work of Shelburne Farms in Vermont and Hancock Shaker Village in the Berkshires on farm education and innovation, the nascent Battle Road Farms at Minute Man National Historical Park in Lexington and Concord, the Billings Farm within Marsh-Billings-Rockefeller National Historic Park in Woodstock, Vermont, and more.

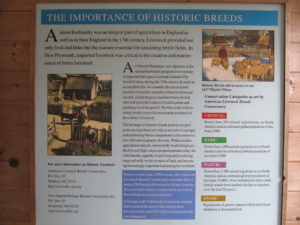

Here at Plimoth, the Rare and Heritage Breeds Program shifts this site’s mission toward the instrumental and innovative, combining the undeniable visitor appeal of baby goats with the preservation and dissemination of heritage breeding stock. As the farm staff and interpretive signage in the Nye Barn make clear, one of the explicit purposes of this program is to help strengthen the resilience and biodiversity of our food systems against the possibility – even the likelihood – of a coming time of scarcity and need.

Here at Plimoth, the Rare and Heritage Breeds Program shifts this site’s mission toward the instrumental and innovative, combining the undeniable visitor appeal of baby goats with the preservation and dissemination of heritage breeding stock. As the farm staff and interpretive signage in the Nye Barn make clear, one of the explicit purposes of this program is to help strengthen the resilience and biodiversity of our food systems against the possibility – even the likelihood – of a coming time of scarcity and need.

And this is where things circle back around for me when thinking about Plimoth. In the context of a changing economic and atmospheric climate, this place appears as not just a mythologized beach-head for European occupation of Native North America. It’s not just a workplace where people struggle to make the usually-avocational practice of living history into both an occupation and a refuge from the harsh effects of a postindustrial economy which may be over-reaching itself – or already have over-reached – to the point that it can’t possibly be sustained.

It begins to appear more as a place to rediscover and incubate old/new knowledges and practices that are potentially in dialogue with emerging movements and infrastructures that challenge large-scale capitalism’s relentless logic and work against the social and environmental damage it has done and continues to do. We may, in fact, be finding ways to re-occupy a set of narratives and meaning that the scholarship of the past few decades has thoroughly de-mythologized, but which may still contain usable ideas about acquiring the tools for subsistence and coexistence in a very specific place in a challenging climate and a time of profound uncertainty and change.